A Complete Program

I can’t remember who said it but there’s a saying about writing that goes something like “One does not complete a book, one abandons it.” Writing programs can sometimes feel similar—you might always think of parts of the interface you could improve or routines you could revise long after the program goes into use.

But a program can reach a stage of completion. A program has a certain purpose, a more or less known goal and various well-defined and expected parts. It should probably receive input, probably process or act on that input in some way, and produce some output. So when the program fulfills that purpose—when its interface is fairly well built out, its supporting functions all debugged and performant, and its output satisfying—you could say that it’s complete. There might still be aspects that could be improved or revised—and there might always be—but, if it does what’s expected of it, then it’s fair to consider the program more or less complete, if not finished.

So let’s go through the process of writing a complete program.

The Problem

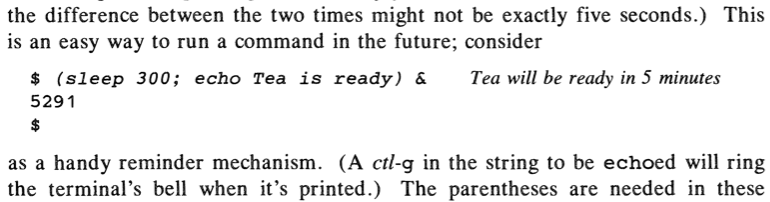

This snippet comes from The Unix Programming Environment, demonstrating a simple timer:

This isn’t really a program—it’s a single compound shell statement that runs two programs—but it demonstrates a solution to the problem that would have worked as intended in the time/context in which it was written, when your use of the computer was channeled through your terminal. It would be less effective today, when we can have multiple terminal emulator windows open in multiple virtual workspaces split over multiple physical screens. So let’s modernize it.

A Minimum Viable Solution

What would a modern solution look like? The end goal of the program—some trigger to let you know that a certain amount of time has passed, potentially tagged to some other task, like steeping tea—might best be handled by sending a notification. So for that we’ll use the notify-send command, which is provided by the Dunst program and which allows us to create notifications with titles, body messages, and variable levels of urgency. For example:

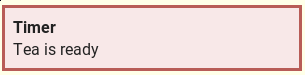

notify-send -u critical Timer "Tea is ready"

will create a notification marked with high urgency, with the title “Timer”, and a reminder of the timer’s purpose.

We’ll need to delay the notification by a certain amount of time. For that, sleep will work.

Putting those together, we have a command like this:

(sleep 180 ; notify-send -u critical Timer "Tea is ready") &

Backgrounding the job will return the process ID, which we can use to cancel the timer if we need to, and will return our command prompt, so the terminal can still be used while the timer runs down.

Improving It

But that’s a lot to type. It’d be nicer if we could reduce that to something like:

timer 180 "Tea is ready"

Here’s a script that can enable that:

#!/usr/bin/ruby

# At least one argument must be given: either a number of seconds to

# delay, or a message.

# Check the number of arguments.

if ((ARGV.length < 1) ||

(ARGV.length > 3))

$stderr.puts "timer: {number of seconds}[ {message}[ {title}]]"

exit

end

# Set some initial/default values.

seconds = "5"

title = "Timer"

message = ""

# Loop through the arguments, set the values as appropriate.

ARGV.each do |arg|

if (arg.match(/^[0-9]+$/))

seconds = arg

elsif (message.length == 0)

message = arg

else

title = arg

end

end

# Fork the process, run the sleep-and-notify command.

pid = fork do

system("sleep #{seconds} ; notify-send -u critical \"#{title}\" \"#{message}\"")

end

# Print the forked process ID number and a confirmation message.

puts "[#{pid}] Set timer for #{seconds} seconds."

Put that in your ~/bin and you’d have a nice and simple timer command.

But is it complete? In general, a program has three parts:

- The interface, being both what functionality is exposed by the program and how someone interacts with that functionality.

- The main job, being the process by which the program achieves the stated goal or the solution to the problem.

- The output, or the result of the main job.

The main job of this program is reasonably complete: after a delay of the given number of seconds, it will create a notification containing the given title and message (or sensible defaults if none are given).

The Interface

But the interface could be improved. For example, it might be nice if we could specify the time to delay in different units, like 3m for three minutes, so we wouldn’t need to convert it into seconds by ourselves. And it might be nice if the program could accept multiple time-delay arguments and sum them all, so we could specify something like 1m 30s for 90 seconds, or 2h 30m for 9000.

Here’s a revision of the program (with comments removed for the sake of brevity):

#!/usr/bin/ruby

if (ARGV.length < 1)

$stderr.puts "timer: (NUMBER[dhms])+ [ {MESSAGE}[ {TITLE}]]"

exit

end

seconds = 0

title = "Timer"

message = ""

ARGV.each do |arg|

if (p = arg.match(/^([0-9]+)([dhms])?$/i))

if ((p[2].nil?) || (p[2].downcase == 's'))

seconds += p[1].to_i

elsif (p[2].downcase == "d")

seconds += ((p[1].to_i) * (60 * 60 * 24))

elsif(p[2].downcase == 'h')

seconds += ((p[1].to_i) * (60 * 60))

else # 'm' is the only remaining option

seconds += ((p[1].to_i) * 60)

end

elsif (message.length == 0)

message = arg

else

title = arg

end

end

if (seconds == 0)

seconds = 5

end

pid = fork do

system("sleep #{seconds} ; notify-send -u critical \"#{title}\" \"#{message}\"")

end

puts "[#{pid}] Set timer for #{seconds} seconds."

If you’re going to allow other people to use your program, it might also be nice to enable a help message via the common -h or --help flags:

if ((arg.downcase == '-h') || (arg.downcase == '--help'))

puts <<~STOP

timer: sleep a while, then send a notification.

To specify the delay time, provide arguments in the form

[0-9]+[dhms]

Here, `d` stands for days, `h` for hours, `m` for minutes, and `s` for

seconds. If no unit is given, `s` will be assumed.

If you provide multiple time-delay arguments, their values will accrue.

So you can delay 90 seconds with `90s` or `1m 30s`.

You can also provide a message and a title to use for the notification.

The first argument given that does not look like a time-delay argument

will be used for the message. The second will be used for the title.

Both the message and title are optional. If neither are given, "#{title}"

will be used as the title, and no message will be used.

Examples:

timer 5m Tea

timer 1h 10m Laundry

timer 45 "Fresh is best" Pasta

STOP

exit

Could the interface be improved further? It now exposes the time-accruing functionality in a sensible and friendly way. And the order of the title and body message arguments is reasonable—with only one string given, the notification will look like:

which is pretty nice. If you want a different title, you can add it:

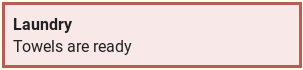

timer 1h 10m "Towels are ready" Laundry

will yield:

Could the program benefit from accepting input via stdin? In general, it’s nice when programs can act on either stdin or named files (e.g., ls -la /usr/bin | less, or less README). But it might not make much sense for this timer. Its input is in a somewhat irregular format, so it’s hard to imagine a situation where piping arguments in is as helpful as typing them out. So let’s not worry about that for now.

But what about its output/result? Would it make sense to enable end functionality other than creating a notification? It’s much easier to imagine a situation when that might be helpful.

Extensibility

I read a quote somewhere on the internet that went something like “extensibility is a euphemism for ‘supports bloating’”. And I’ll give it points for being witty and sharp, but the thought it contains is wrong.

Extensibility is a core tenet of the Unix Philosophy: “Write programs to work together”. One way to achieve this is to make your program “do one thing and do it well” and “handle text streams”—it can then be used in any chain of commands the user needs. Another way (which we’ll use for this timer program) is to enable your program to call other programs. In this way, even if it’s not pipe-able, it can still be chain-able, linking out to whatever command you want.

For the timer, we’ll enable custom end commands with the -c or --command options. The command will be expected as the argument immediately following that option. So we’ll need to change our default values and loop construct from:

ARGV.each do |arg|

...

end

to:

command = ""

i = 0

while (i < ARGV.length)

arg = ARGV[i]

...

elsif ((arg.downcase == '-c') || (arg.downcase == '--command'))

command = ARGV[(i + 1)]

i += 1

...

i += 1

end

And, since it’s conceivable that the custom command might want information from the timer, we’ll pipe the notification’s title and message into that command’s stdin:

if (command == "")

command = "notify-send -u critical \"#{title}\" \"#{message}\""

else

command = "echo \"title: #{title}\nmessage: #{message}\" | #{command}"

end

And change the forked command:

pid = fork do

system("sleep #{seconds} ; #{command}")

end

Cleaning Up

So right now our program is pretty ugly:

#!/usr/bin/ruby

if (ARGV.length < 1)

$stderr.puts "timer: (NUMBER[dhms])+ [ {MESSAGE}[ {TITLE}]]"

exit

end

seconds = 0

title = "Timer"

message = ""

command = ""

i = 0

while (i < ARGV.length)

arg = ARGV[i]

if ((arg.downcase == '-h') || (arg.downcase == '--help'))

puts <<~STOP

timer: sleep a while, then send a notification via `notify-send`.

To specify the delay time, provide arguments in the form

[0-9]+[dhms]

Here, `d` stands for days, `h` for hours, `m` for minutes, and `s` for

seconds. If no unit is given, `s` will be assumed.

If you provide multiple time-delay arguments, their values will accrue.

So you can delay 90 seconds with `90s` or `1m 30s`.

You can also provide a message and a title to use for the notification.

The first argument given that does not look like a time-delay argument

will be used for the message. The second will be used for the title.

Both the message and title are optional. If neither are given, "#{title}"

will be used as the title, and no message will be used.

The notification will be sent via `notify-send`. If you'd like to run a

custom command instead, you can specify that with the `-c` flag, e.g.,

`-c "path/to/command"`. Information about the timer will be passed to

the command via standard input.

Examples:

timer 5m Tea

timer 1h 10m Laundry

timer 45 "Fresh is best" Pasta

timer 30d "Up 30 days" -c "~/bin/post_uptime_notice"

STOP

exit

elsif ((arg.downcase == '-c') || (arg.downcase == '--command'))

command = ARGV[(i + 1)]

i += 1

elsif (p = arg.match(/^([0-9]+)([dhms])?$/i))

if ((p[2].nil?) || (p[2].downcase == 's'))

seconds += p[1].to_i

elsif (p[2].downcase == "d")

seconds += ((p[1].to_i) * (60 * 60 * 24))

elsif(p[2].downcase == 'h')

seconds += ((p[1].to_i) * (60 * 60))

else # 'm' is the only remaining option

seconds += ((p[1].to_i) * 60)

end

elsif (message.length == 0)

message = arg

else

title = arg

end

i += 1

end

if (seconds == 0)

seconds = 5

end

if (command == "")

command = "notify-send -u critical \"#{title}\" \"#{message}\""

else

command = "echo \"title: #{title}\nmessage: #{message}\" | #{command}"

end

pid = fork do

system("sleep #{seconds} ; #{command}")

end

puts "[#{pid}] Set timer for #{seconds} seconds."

To the user it’s looking nice enough because its interface is predictable, friendly, and mnemonic. But remember that “Programs must be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute” (Harold Abelson, Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs). So, before we can consider our program complete, we should make it more reader-friendly. Here’s a version I’m considering complete enough to abandon.

Some might see the expansion of a single compound command into a nearly 200-line script as a sign of everything wrong with modern software development. And, on one hand, that’s a fair point. But, on the other, the result is pretty nice.