An open letter about classical music to people who know far more about classical music than I might ever know

Last week, Alex Ross tweeted a link to an article on Gramophone magazine by Philip Clark whose headline asks “What’s wrong with the classical concert experience in the 21st century?”, and whose answer to that question is, essentially, not one God damn thing. Toward the middle of the article, Mr. Clark expands the applicability of that answer from the concert experience to the purported “image problem” of classical music in general: “there is absolutely nothing wrong with classical music”, he writes, except for maybe the way we talk about it.

I don’t know much about classical music—aside from a couple “music appreciation” classes in college, everything I know has been gleaned from magazine articles, reviews, podcasts, Wikipedia, and The Rest is Noise—so feel encouraged to disregard this as you would any other random opinion on the internet. But I like classical music, I’d like to know more about it, and I think there are a few problematic aspects of it beyond the way we talk about it. Though that is a big one.

Here are the things I’ll discuss:

Digital players

One frustrating aspect of listening to classical music has nothing to do with the music itself, but with the experience of interacting with that music on our digital devices.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, digital music players (Winamp, iTunes, VLC, etc.) presented songs in a sortable table with each row containing the song’s name, album, artist, and maybe a couple other points of data. These players instilled a gross mental dissonance between music—our most vital, dynamic, and pervasive form of art—and a spreadsheet. The expansion of metadata to include composers, etc., made it easier to filter through this spreadsheet, which became the new face of your music library, and the addition of album art and psychedelic visualizations enhanced the presentation a little, but aside from that the experience has not substantially changed in fifteen years.

Physical formats allow for personalized interaction. You can read the liner notes as you carry the album to the player. You can face the best covers outward. You can arrange your albums in exactly the way you want them—a pile of new acquisitions, a pile of this week’s favorites, a stack of recommendations, a stack containing songs you might include in a mix. You can sort them according to genre, according to how you learned about them, according to likeability, alphabetically, autobiographically. All these actions and associations reinforce our relationship to the music.

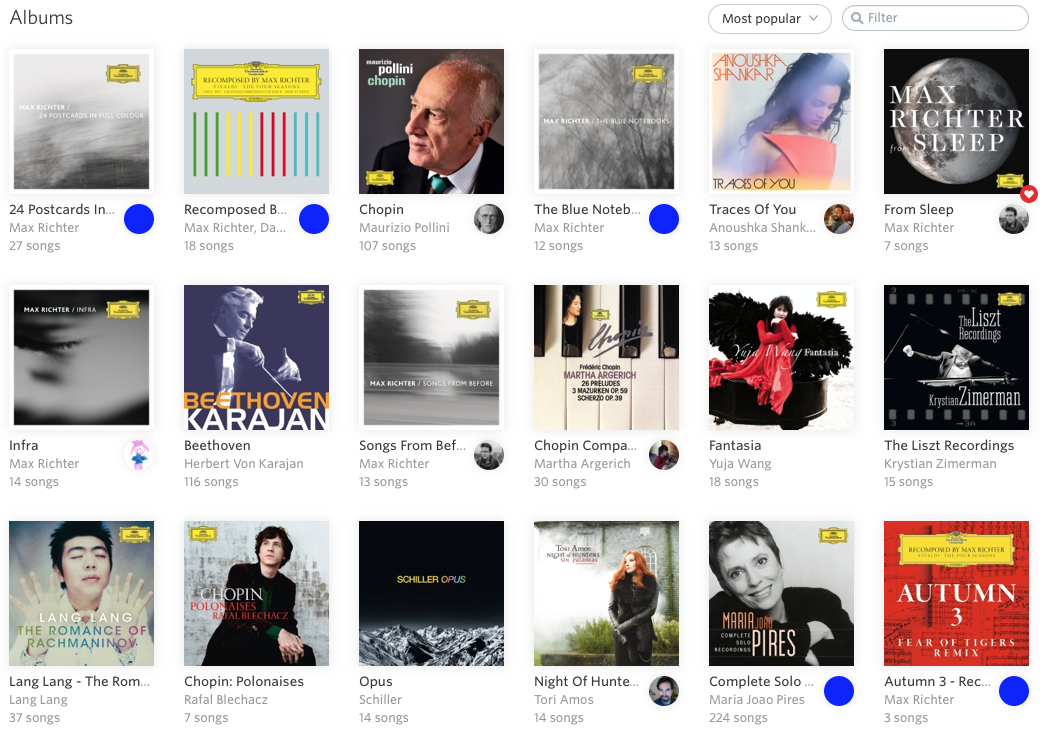

Thanks for the image.

Digital players, on the other hand, by necessity limit your interactions to the presentations and behaviors enabled by the player’s designers and programmers. None that I know of allow you to order albums in arbitrary ways. Most will display the album art or tint the interface to match the art’s color scheme. All of them provide a tabular interface. The iTunes of today is a much richer experience than the Windows Media Player of 1999 but the lion’s share of that enrichment came in the form of the iTunes Store. Apple built an application for buyers, not collectors.

I’m not advocating physical formats over digital, but a revision of our players and an expansion of their interfaces and the interactions they enable. A great digital music application would be about 10% player, 90% library.

Streaming services provide great alternatives to broadcast radio stations but their organization and search features are often much more anemic than their non-streaming counterparts. For example—I’ll pick on Rdio because I pay for their service—it doesn’t appear that Rdio factors composer metadata into their search results at all. A search for “Morton Feldman” returns albums that list him as the artist or songs that include his name in the title—the album American Elegies appears because the eighth track is titled “Morton Feldman (1926–1987): Madame Press Died Last Week At Ninety”. But a search for “Mahler San Francisco” does not return the San Francisco Symphony’s Masterpieces in Miniature even though Mahler’s “Blumine” is the second track. Rdio appears to give Mahler no credit whatsoever on that album. And when a composer’s name exists, it is attached sloppily and unevenly.

But it’d be absurd to blame these poor experiences solely on the software designers. Robust organization and search features require robust data models, but even if the model is robust it will appear weak if it’s not given the data it needs. So if search results are weak, is it because the programmer’s model is weak or because the label didn’t provide the data? Who’s to blame for all the gross grey squares in my iTunes—Apple, Deutsche Grammophon, or myself?

And if we wanted to blame software designers, we should reserve sympathy for those building streaming services. The survival of those services relies on subscribers, and it makes sense that the service provider would focus on providing the greatest possible service to the greatest number of their subscribers. If, statistically speaking, their subscribers don’t much care about composer metadata, then justifying the expense of enriching their data models or filling in data where it’s missing might be impossible. Apple and Microsoft don’t get to use that excuse.

A few simple conditions could result in a much better presentation:

- If composer or performer metadata is present, display it.

- If all the tracks in an album are by the same composer, then display the composer’s name near the album title. If there are multiple composers, display their names next to their tracks. Use the same procedure for performers.

- If there is album art, display it. If not, fall back to nice typography. Maybe choose a typeface depending on the genre, if that metadata exists. If not, just choose a good one, or allow the user to specify their favorite in the application’s settings. Anyway, do not display a big blank square.

- When building an “Up Next”-style playlist, intelligently deduce whether the user wants to queue a song or the entire album, and whether the album they want to “Play Next” means “after this song” or “after this album”.

- Allow the user to organize albums and songs in any way they want.

The files in a digital album usually include the album art and all the metadata you’ll ever need but they don’t often include digital booklets. And even if they do, music players don’t enable easy access to those booklets. They could.

The entire experience of digital music players could be much richer. In a historical view, we’re still in the early days of digital media and graphical user interfaces. They’ll get better. To use a video game analogy: our current players are platform games. We could have an open world.

By the by, if anybody wants to fund the development of a better music player, I’d be happy to build one.

But disappointment with our music players doesn’t extend to the music itself—I’ll love “Rhapsody in Blue” even if iTunes depicts it as a gross grey square.

Image, perception, and appeal

When someone says that classical music has “an image problem” I assume they’re talking about its popular perception. But part of me suspects they’re really talking about its popular appeal.

The popular perception is that classical music is for the old and intelligent, that playing it at a party will bore your guests but playing it for your babies might make them smarter, that talking about it might make you seem sophisticated, maybe a little aloof, definitely a little irrelevant. When you imagine a fan of classical music you see a grey man in a black suit, a grey woman with white hair, a middle-aged music instructor, or a teen-aged student who might some day perform for a crowd of those grey people. Overall, this is not a bad perception, especially compared to the popular perceptions of fans of electronic dance music or death metal. You’d probably rather be seen as a sophisticated geezer than a Juggalo.

The most intractable aspect of that perception is the irrelevance. In this context, here are four things relevance can mean:

- The ability to relate to or feel something from the music.

- The ability to relate to other people through or with the music.

- The historical understanding of how that music relates to contemporary music.

- How often you listen to or otherwise encounter the music.

Obviously, to someone who performs, studies, or writes about it (except for letters like this, of course), classical music would be highly relevant on all four counts. But for the rest of us, even for those of us actively expanding our familiarity with it, the decline can be fast and drastic.

For years I listened nearly exclusively to electronic music. On a good Saturday my friends and I would go shopping for records during the day and find a warehouse party that night. During the week we would make mixes, listen to taped radio shows, download whatever records we couldn’t find at the stores from Napster. We could subject any fool to a lecture on the myriad minuscule differences between goa trance, psy trance, deep house, tech house, dub techno, Detroit techno, Miami bass, drum and bass, intelligent drum and bass, intelligent dance music, on and on, to stupidity and beyond. It was great. We were our high school’s reigning experts on the scene.

These days I listen to a lot of classical music. I feel like a neophyte again. It’s great.

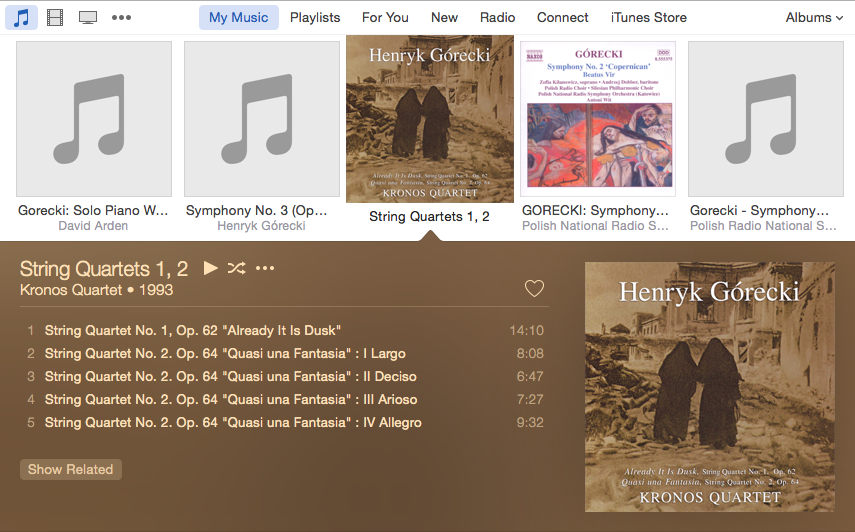

The road I followed from the warehouse to the opera house was paved with music by Aphex Twin, Eric Satie, Arvo Pärt, Philip Glass, Rachel’s, Brian Eno, Henryk Górecki, Stars of the Lid, Chilly Gonzales, and Nils Frahm.

From an interview with Rolling Stone:

Interviewer: Guys like Avicii, Calvin Harris and Zedd are all over the radio.

Aphex Twin: It’s a way in for people, isn’t it? That’s a start, the commercial things. And if you’re really into it, you can look further, investigate and find people like me [laughs].

From Philip Clark’s article on Gramophone:

… we need to … refuse to accept the doublespeak that any of this pretendy classical music represents any future at all. We need to speak up for classical music, and defy the idea that video game music is, as I once heard a classical music exec say, ‘the new classical’.

Mr. Clark uses the term “pretendy classical music” to describe the work of, specifically, Max Richter and Ludovico Einaudi, and, presumably, anyone signed to Erased Tapes. Mr. Clark knows far more about classical music than I might ever know but on this matter I need to express a respectful disagreement and side with Aphex Twin. There’s plenty of value in pretendy classical music. The leap from goa trance to Gustav Mahler is far too great for mortal listeners—pretendy classical music can bridge the gap. It’s easy to take the step from Rachel’s Music for Egon Schiele to John Tavener’s Towards Silence, from A Winged Victory for the Sullen to Górecki’s Third, from Music for Airports to “Rothko Chapel”. For the curious listener, these gateway records open doors to paths they might not have otherwise discovered. And if the record’s great enough it’ll open the door, pull the listener in, and quietly close the door behind them after they’ve gone charging down the hall.

For years my teenage brothers were (they still might be) obsessed with Minecraft. They’d listen to its music even when they weren’t playing the game. One of them has recently branched out to other not-quite-ambient, not-quite-danceable electronic music. I look forward to introducing him to James Blake, The Orb, and Boards of Canada. Some day he might love the underappreciated masterpiece Drukqs almost as much as I do. But we’d never get there if it weren’t for the garbage he’s listening to right now.

I agree wholeheartedly with Mr. Clark that video game music is not and should not be the future of classical music. And I don’t think classical performers need to start compromising their performances with pretendy classical music solely in the effort of attracting new, younger audiences. Neither do I think pretendy classical music has no value aside from acting as gateway records (I love Erased Tapes). But video game music and pretendy classical music both, step by step, can increase classical music’s relevance, at least the items 1, 2, and 4 from the list above. Pretendy classical music clearly has a popular appeal lacking by the genuine article.

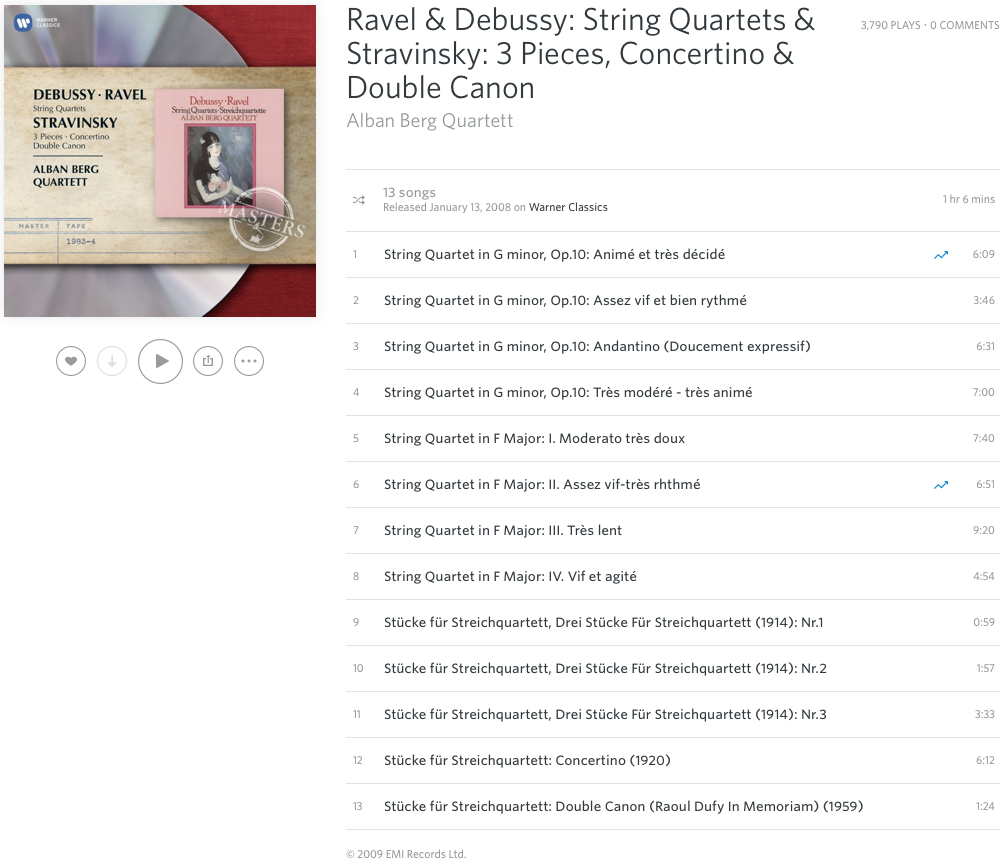

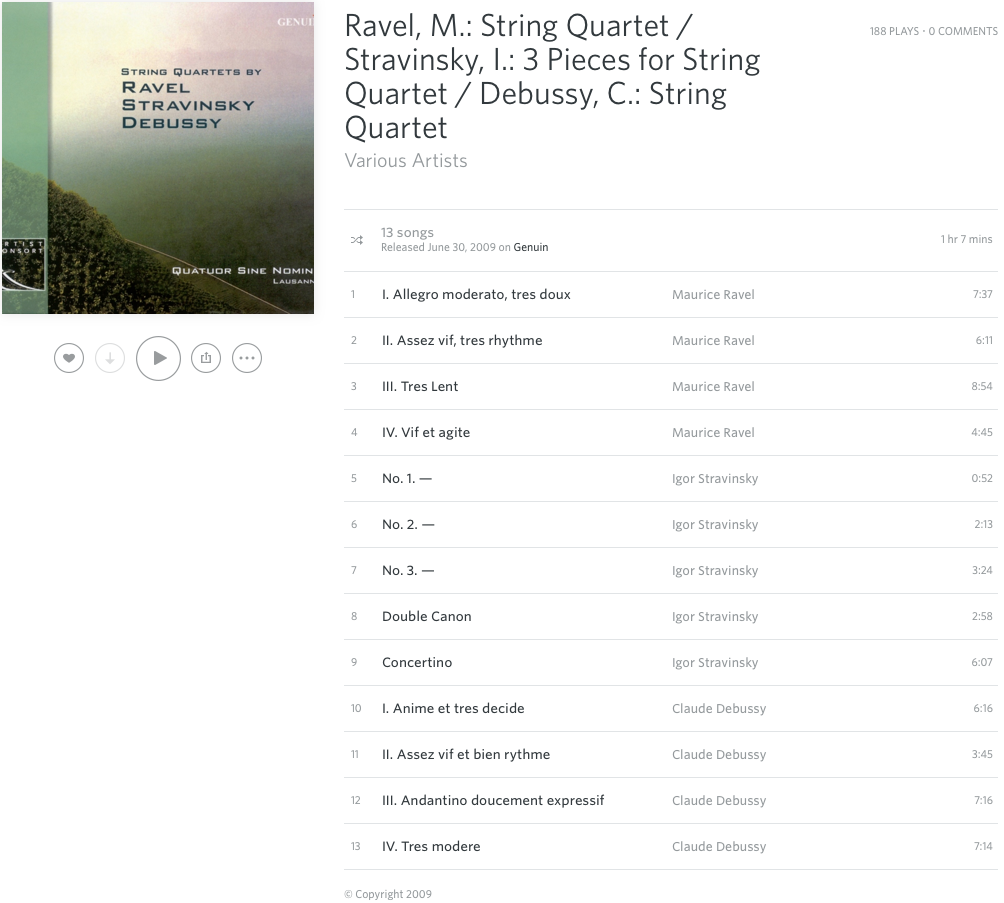

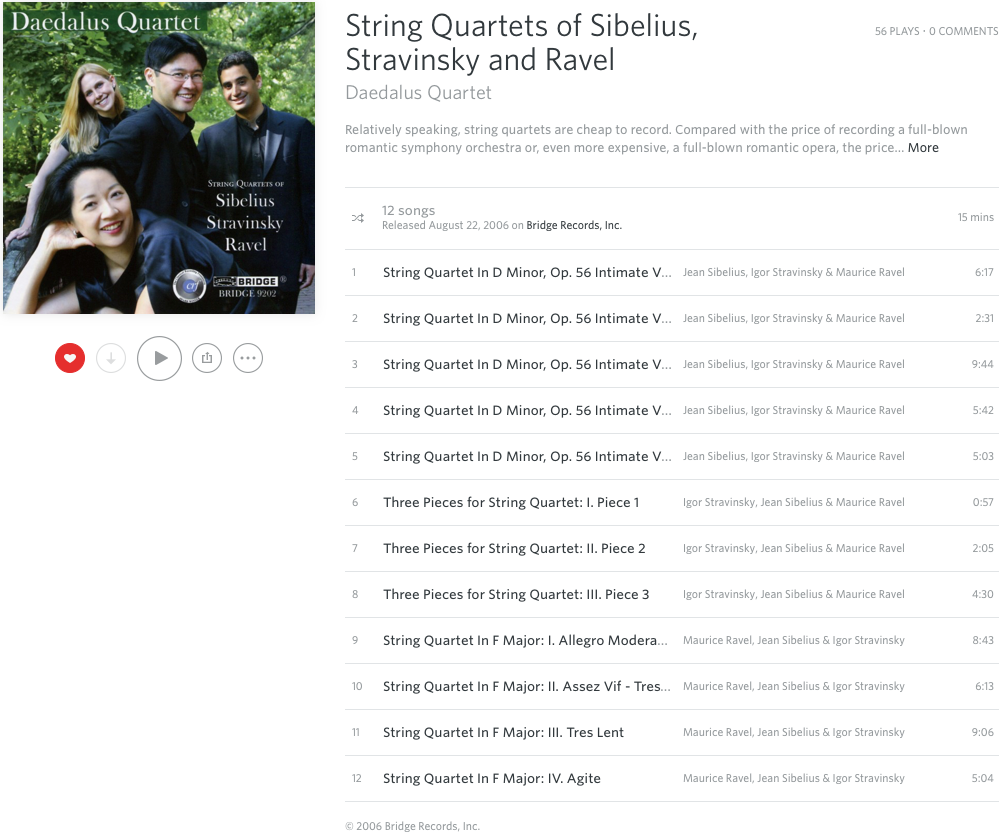

Well-designed compilations could help with item 3 on the relevance list—a curated collection of works that link the past to the present. Together with a booklet explaining the reasoning behind and connecting each selection, it could be edutainment at its finest. From Frahm to Brahms. This compilation includes Ellington and Gonzales and Messiaen and Cage and moves seamlessly between them. I play it often. My only complaint is that it includes no notes. It’s common to see a compilation of string quartets—the trio of Debussy, Stravinsky, and Ravel seems particular popular—but less common, at least to my knowledge, are compilations that connect contemporaries with historical precedents, like Rothko Chapel: Morton Feldman, Erik Satie, John Cage.

We do not need more compilations like “Piano Chillout”, “Top 300 Essential Classical Masterpieces”, and “All-Time Best of the Baroque”.

But, speaking of design, a lot of classical labels could use some help with album art and branding. When I see Deutsche Grammophon’s gold stamp, in any of its variations, I know I’m probably in for something special. ECM New Series typically looks great—stark, but fitting. Naxos’s design reminds me of Penguin Classics. I’m much more drawn to paintings by Matthew Ritchie, creepy trees, strong typography, and thematic variations than I am to smiling men, movie allusions, or numbers in lightning. If classical music has an image problem, then album covers present a simple, literal opportunity for renovation.

Concerts

But the headline of Mr. Clark’s article asks about the concert experience. And I agree with nearly every point in his answer: the music should remain the focus, lame gimmicks are lame, and I’d never not go to a concert because I didn’t know exactly when to clap. But I also agree with Yannick Nézet-Séguin, whom Mr. Clark quotes in his article: “It’s all about communication.”

Mr. Clark focuses on Tom Morris’s idea, at a performance of Beethoven at the Bristol Proms, of projecting the faces of the performers so the audience can watch them emote while they play. This idea may not be the best but I wouldn’t discourage Mr. Morris from considering others. Watching a violinist’s face wouldn’t teach me anything about the music or deepen my appreciation of it—it would just give me something to watch while the music played—but a brief discussion of the music could certainly increase its relevance. Especially if the speaker has the eloquence and sultry voice of Leonard Bernstein.

When digital technology enables us to listen to the highest-quality recordings of our favorite works anywhere we are, the challenge of the concert hall becomes how to draw us out of our homes, out of our headphones. And, though I agree with Mr. Clark that the music should remain the primary focus of the concert experience, it’s undeniable that the other aspects factor into the experience.

So it’s important to find a compelling match between music and location. Arvo Pärt’s Alina is the first classical record I bought, and “Spiegel im Spiegel” remains one of my favorite pieces, but it might be a poor fit for a concert hall. And I can’t say surely, even if it were to appear on a program, that I would make the effort to attend. But Mr. Pärt’s “Credo” would be a must-see. The Metropolitan Museum’s Temple of Dendur concert in celebration of his 80th birthday was a great idea, an excellent union of program, occasion, and location. I wish I could have been there.

As Mr. Ross showed us, price is not necessarily a prohibitive factor in attending a concert. But other economic factors, especially as they pertain to taste, might prevent the attendance numbers from growing. Especially in smaller cities, like my home of Portland, Oregon, I imagine that the symphony would rather invest safely and avoid potentially risky propositions like Pärt’s “Credo”. I have no right to blame the Oregon Symphony for their program choices, and a few of this season’s concerts look appealing, but I’d much rather attend a performance of music that inspired movies than music composed for the movies.

Talking about it

Mr. Clark wrote this about about the term “classical music”:

… we need to be far sharper in our definition of what classical music actually is. Just as the word ‘jazz’ has become an envelope term applied haphazardly to all points between Frank Sinatra and the wildest frontiers of free improvisation, ‘classical music’ has come to symbolise everything from Machaut motets to the musique concrète of Pierre Henry, from André Rieu to Pierre Boulez—it’s all, somehow, ‘Classical’.

And he’s absolutely right.

Part of my experience with electronic music was to develop a robust vocabulary about it. It annoyed me that everyone just called everything “techno”. There are names for every imaginable microgenre and there are terms for every component of a song, from the buildup to the amen breaks to the breakbeats to the drop. This vocabulary enhances our ability to relate to the music, to analyze and discuss it—our words make us better able to recognize any given song’s structures, dynamics, adherence to genre norms and deviations. Our appreciation of the music grows in step with our ability to talk about it. We use these terms and invent categories not to diminish the music but to intelligently grow our love for it. As Richard Feynman said in a related discussion, “It only adds. I don’t understand how it subtracts.”

When it comes to public appreciation, the number of words written on a subject is a much better metric than the volume of dumbstruck smiles. But as for which terms we should start using, I’ll respectfully defer to the experts.