Debugging a Bench

Behold: The Chop Seat.

It’s a little piece of brutalist furniture I made mostly to prove a point but also to prototype the idea before building a larger, nicer version.

This post is a project retrospective and debugging session. Mistakes were made in every phase—requirements-gathering, designing, and execution—which, for the sake of Quality and Truth, Progress and Goodness and every other sense we hold dear, must never be repeated!

Background

Our porch needs some love. One side is occupied only by hanging baskets filled with the shriveled skeletons of dead bouquets—it’s lifeless in multiple ways. But not much will fit there—it’s a smallish, thinnish space, exposed to the street, between the front door and the north side of the house.

The other side is better. It’s a longer space, running along most of the front of the house, protected from the street by a low wall. This is where we sit in the summer—or where we would, if we could. The previous owners left us two plastic Adirondack chairs, one of which shattered last summer as a friend sat on it.

Inside the house, along the same wall as this good side of the porch, is a couch. Most nights, I lie on this couch to read. During the summer of 2023 I would read out on the porch—mostly to keep an eye on the couple living in their Subaru across the street, chopping bikes, selling and consuming drugs, relieving themselves in the bushes, setting things on fire in the street, screaming all night, etc—but, without an enemy to annoy, I retreated to the greater comfort of the couch. I’d like to go outside on summer nights but, on the other hand, I’d rather lie down to read, even if it means being inside, than sit on that plastic chair.

Hence, a project: make a bench, long enough to lie down on, sturdy enough to support a few friends.

But I know myself. I want a good bench. It doesn’t need to be a Craftsman-quality masterpiece but it needs to be clearly better than the plastic garbage we inherited.

But there’s a problem: I’m not a great woodworker, so I need to work up to it. I needed a prototype. A practice piece. Something to build, critique, and improve upon.

Hence: make two benches: one for the side with all our dead plants, one for the side we’ll enjoy in the summer.

The Project(s)

So the small bench comes first.

From the start, there were a number of constraints.

- It shouldn’t cost much. This is a practice piece, after all.

- It should be easy to build. The cuts can be done only with a chop saw, the joins made only with screws and a power drill.

- The big bench should clearly be a scaled-up, nicer version of the small bench. At very least there should be a strong family resemblance between the two.

So I needed the design to be simple and forgiving, easy to conceive, easy to cut and construct, and I needed the material to be cheap, strong, and weather-resistant.

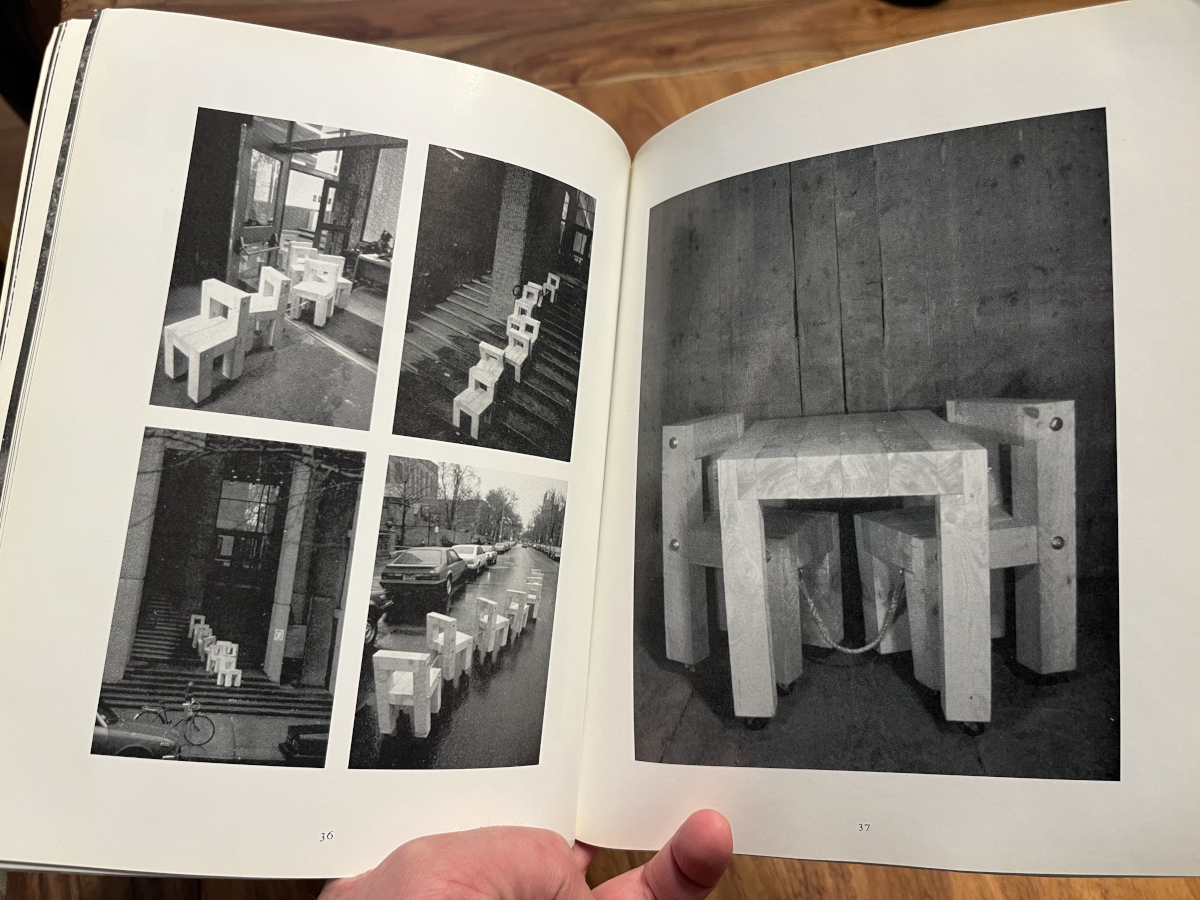

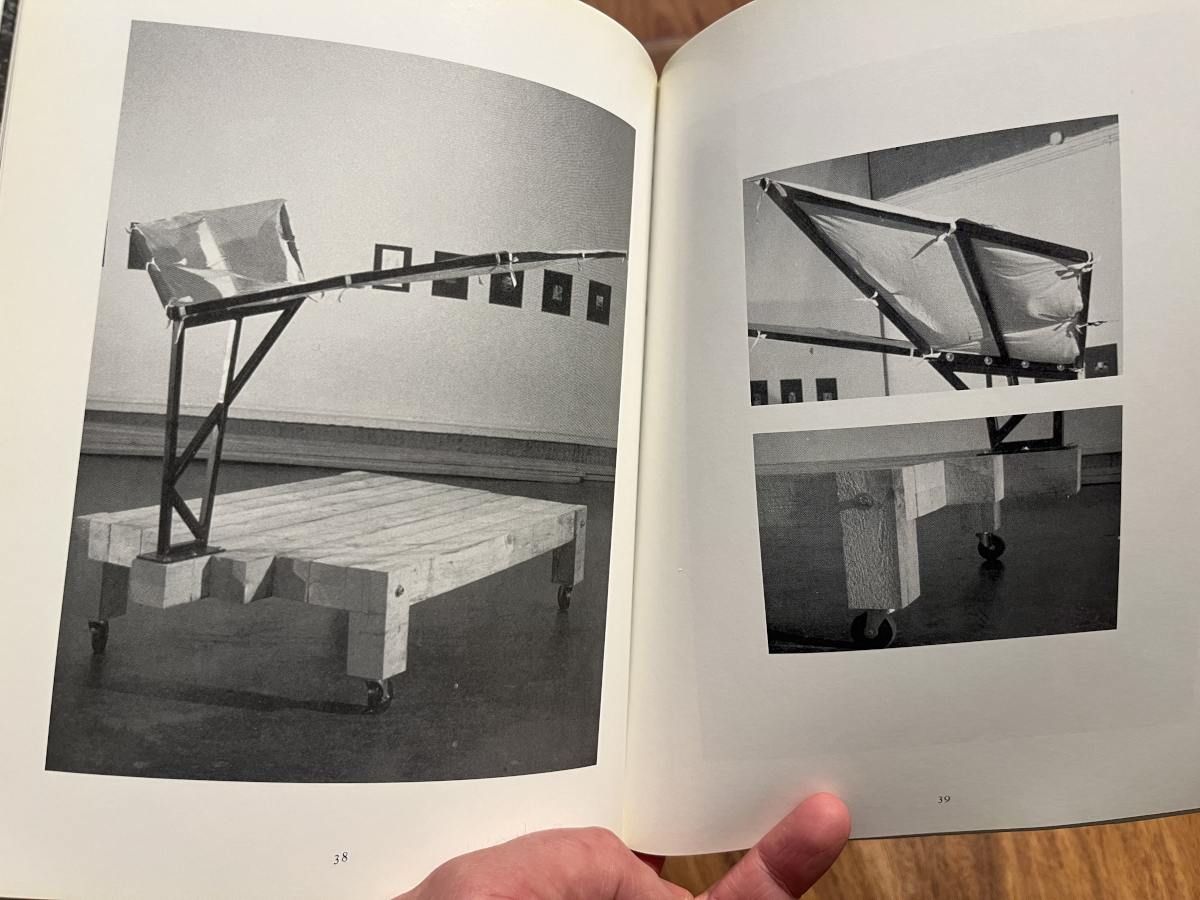

It happened that, as these ideas were starting to form, I read Pamphlet Architecture 17: Small Buildings by Mike Cadwell, which served as a major inspiration.

The Retrospective

The retrospective is in three parts:

- What went well?

- What did you learn?

- What could be improved?

And it refers to these different parts of the bench:

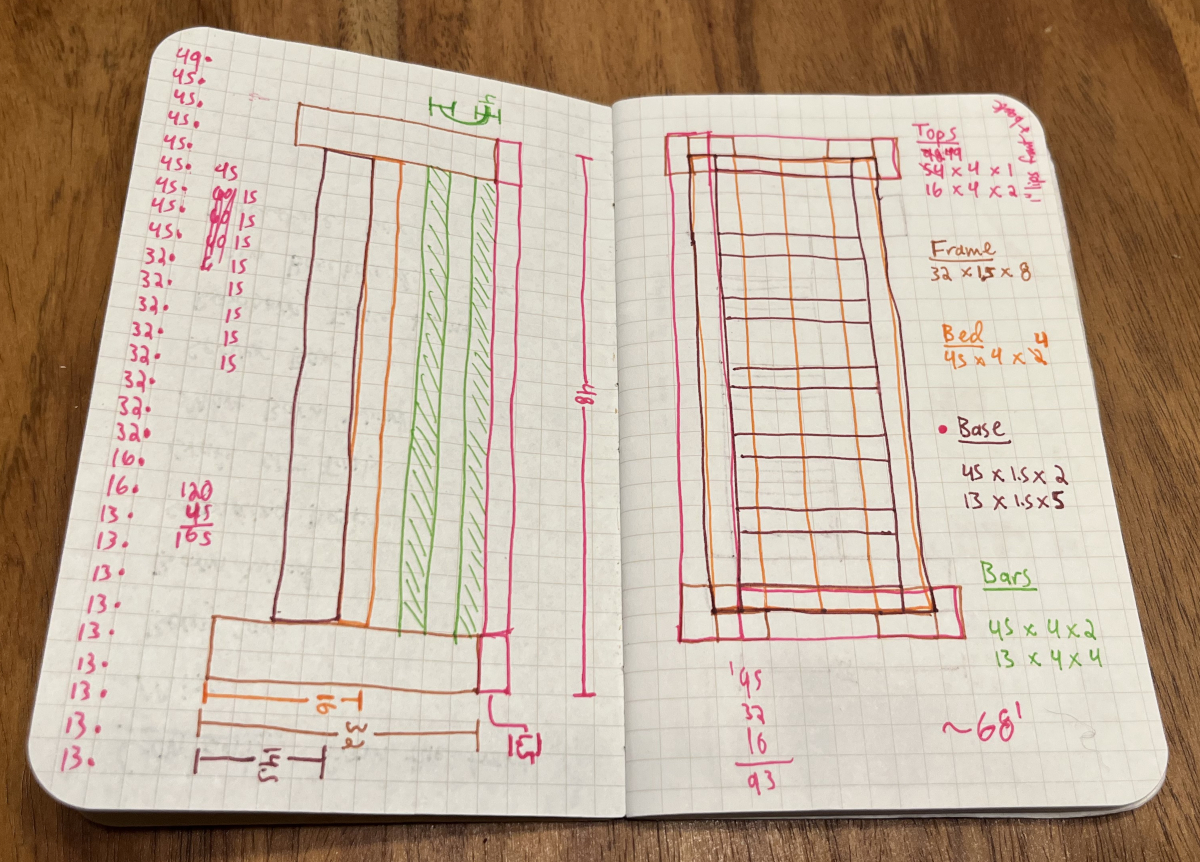

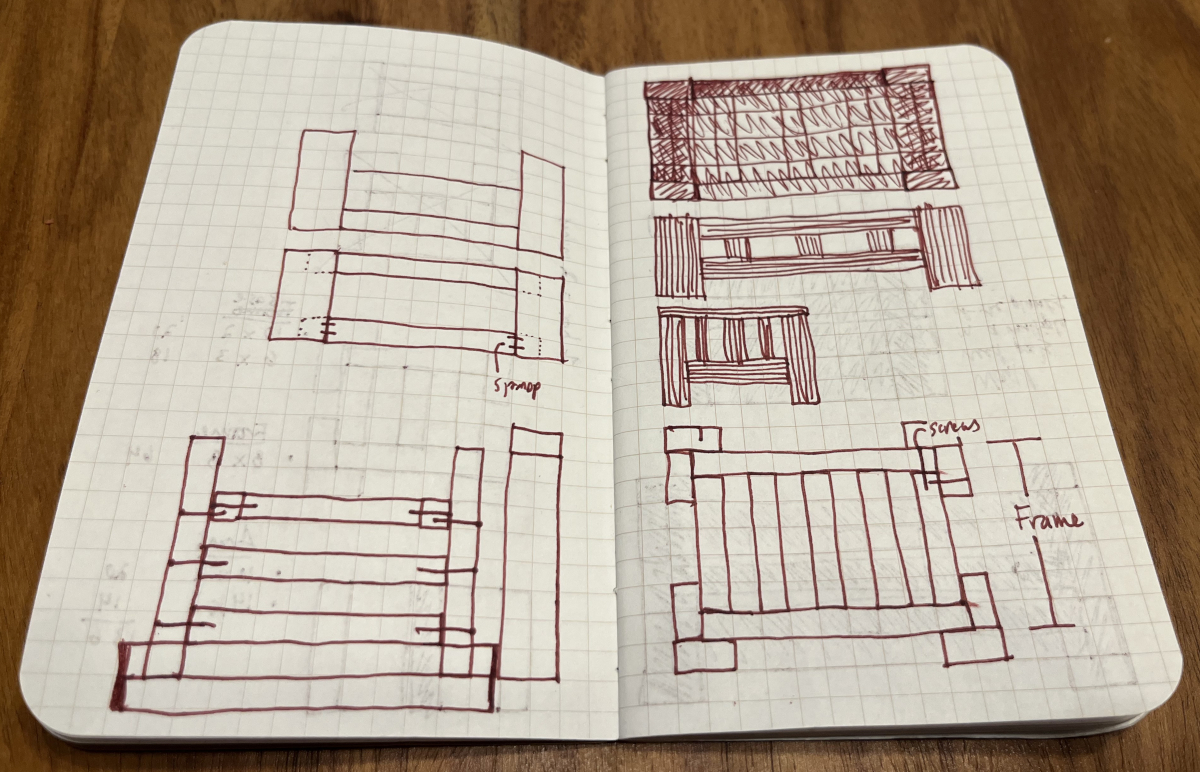

- Tops: the horizontal beams along the top.

- Frame: the vertical beams along the outside.

- Bed: the horizontal beams you sit on.

- Bars: the beams connecting the frame between the bed and tops.

- Base: the beams that support the bed.

What went well?

Most importantly, the idea proved out. The small bench is done, the big bench can be built. The design and construction process is a fine fit, given the constraints.

The bench is super sturdy and, all things considered, looks agreeably nice.

It came in under budget. For this one, I used cedar posts, like you’d use for a fence. Maybe Mr Plywood was having a sale, I don’t remember, but I ended up buying 12 posts for less than $100.

The construction was easier than I expected. Even given the constraints above. The only supplies you need are: lumber, a measuring tape and pencil, a chop saw, a power drill, and screws.

The Southeast Portland Tool Library is awesome. I highly recommend you find and join or start one in your neighborhood.

Planning on paper is nice, and graph paper especially so. No software is needed. It’s quick and easy, as guided or freeform as you want to be.

Side note: as a technology for sketching ideas, making lists, planning personal projects, and so many other things, pen and paper are superb. Not to think of pen and paper as a technology, or to think that software always beats pen and paper in all these ways, requires a kind of blindness, a kind of tool-stupidity, that software people (including myself) seem especially susceptible to.

What did you learn?

The most impactful learning is simple, practical, and bewildering: lumber sizing is a lie. A quote-unquote 2" x 4" is not two inches thick by four inches wide, it’s 1.5" thick by 3.5" wide. Why do we do this to ourselves?

The design is not the thing. During design it’s easy to focus too much on the design, the drawing, as a drawing, and to forget that the whole point of the drawing is to help you think more clearly about the reality of the thing you want to build. This might be especially true when drawing on grid paper—I found myself drawing along the grid, thinking that 2" x 4"s were actually that size, which grids so nicely and makes drawing to scale so easy. That regularity can be too alluring, and you must resist it when need be.

In other words, the design is intermediate, and it’s crucial to stay focused on the end goal.

Related to both of these issues—mostly the lumber sizing, but also focusing too much on the design—the beams of the frame and tops align nicely, but that created a half-inch gap on the inside between them and the bars. I should’ve aligned the bars and tops, since that’s what you lean on, and the interface is the most important part.

That said, expecting perfection is unrealistic. A little roughness is okay. Tiny gaps between the bars and parts of the frame, etc, are perfectly acceptable.

On the other hand, to combat or mask disappointing irregularities, introducing some artful irregularities might be nice. For example, in the current design, the bars of the sides all meet the bars of the back—it might be nice to alternate them, so every other bar meets the frame instead.

What could be improved?

The bench is shallow. This bug relates to two learnings: the one about lumber sizes, and the one about designing with grid paper. Two improvements would prevent this. One: adding another beam or two to the bed. Two: decoupling the bed from the base—in other words, making the base extend beyond the bed in the back, to accommodate the back bars, and not to stack those bars over the bed.

It’s also not quite wide enough. Despite measuring the space to fill before designing it, I unwittingly made it short to fit the grid I designed it on. In other words, I let the grid influence the design. Which isn’t bad in principle—I let the constraints of the saw and the drill influence the design—but, in this case, it created bugs.

As discussed above, there’s a lip on the inside, which is uncomfortable. Given that there must be a lip (1.5" x 2 = 3“, not 2” x 2 = 4"), it’d be better if it was on the outside. A revised construction procedure would prevent this—attaching the two beams of each part of the frame to the base first, then to each other, then capping those with the tops.

The top back beam is a little long. Again, due to not knowing about lumber sizing. It could be trimmed.

Some wood split. This seems inevitable, though I wonder if the cheaper wood I used for the small bench is more likely to split than the nicer wood I’d use for the bigger one.

It still needs to be sanded. And stained and sealed with a top coat. Someday.

Wrapping Up

I feel like this design is one practically anyone could implement. It’s simple and cheap, and rewarding to do yourself—in all, a much greater return on your investment than some cheap thing from Wayfair or Ikea.

This quote from Small Buildings captures some of my experience in both building this bench and writing software, especially when in the flow state:

The only operative principle is to approach building respectfully, so the things of architecture supercede ideas about architecture. I have found that the work takes on its own momentum and one need only be quiet and pay attention. It is mysterious and liberating.

—Mike Cadwell, Pamphlet Architecture 17: Small Buildings

Also, this whole process substantiated the fact that the things we make are tools for happiness. Every single thing we make—a bench, a painting, a computer, a gun—is a means to increase someone’s happiness. So if a thing doesn’t please you, get rid of it. And shed no tears over a broken plastic chair—its breaking is a call to make something better.