On Indices

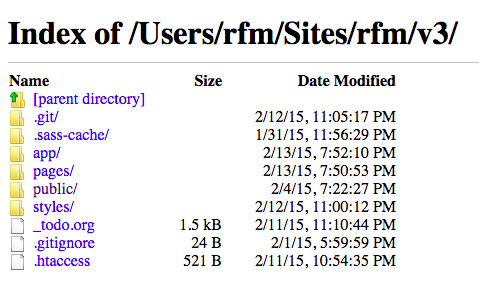

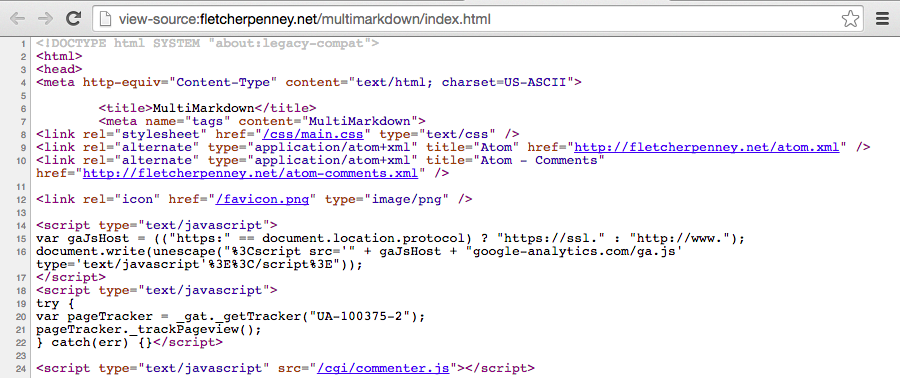

A directory doesn’t look very interesting in your web browser.

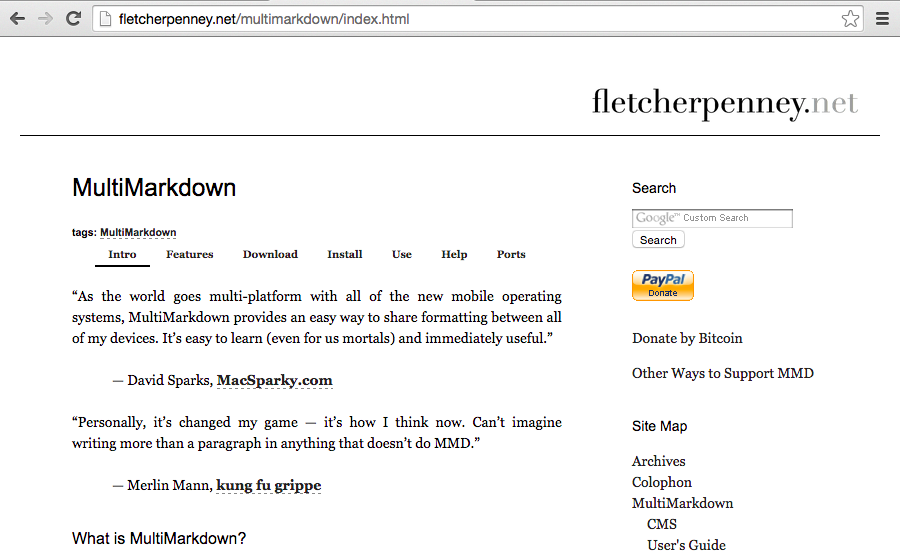

It’s just a list of that directory’s contents. So, when you request a directory, a web server will usually look for a file within that directory named index.html. And if that file exists, you’ll

see that file instead.

Becomes:

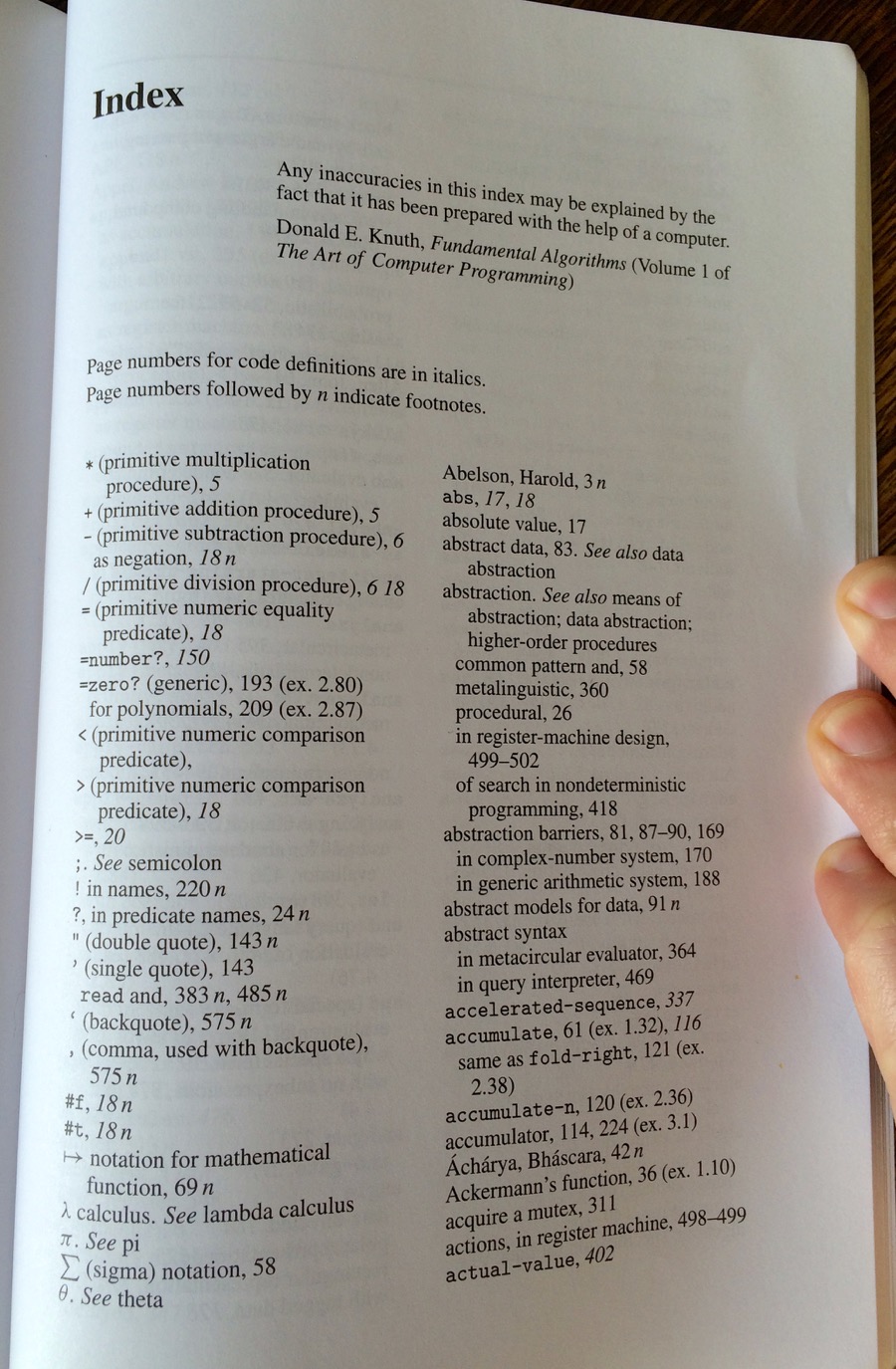

But—like you did, I hope—I started reading books long before I started reading the internet. In a book, an index functions very differently.

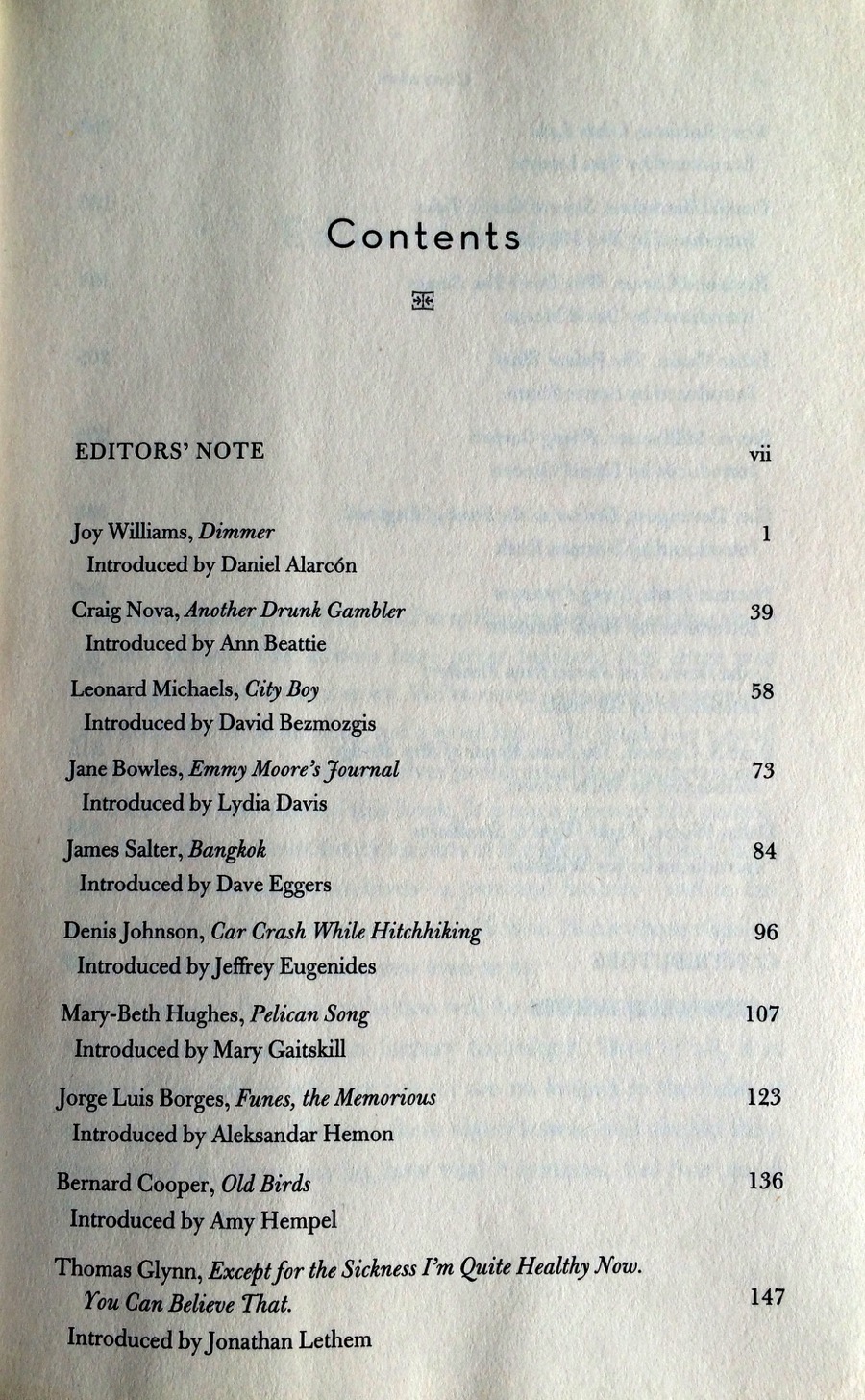

In a book, an index helps you navigate by topic: topics are listed alphabetically alongside numbers indicating the page to turn to.

A table of contents functions similarly, except the list is of titles and they’re ordered as they occur in the book.

So, on a website, a directory list functions more like a table of contents than an index. And the closest most sites get to an index is a tag page, or maybe a tag cloud. And index.html can be whatever you want it to be.

An index is part of a book’s back matter. A table of contents is part of the front matter. Movies and records and magazine articles also have front and back matter—a cover image, a credits list, a bio blurb and references to the author’s best sellers. An article on a website will have front and back matter on multiple levels: the title and author’s name are front matter for the article, the home page—formerly known as the index page—is front matter for the site, and the HTTP headers are front matter for the stream of data the server sends to your computer.

This splitting of information into preliminary, primary, and ancillary material operates fractally and transcends media, culture, and time. In a way, the first verse of the Song of Songs is front matter:

The song of songs, which is Solomon’s.

So that’s why there’s no navigation on this site beyond links to a table of contents and an index.